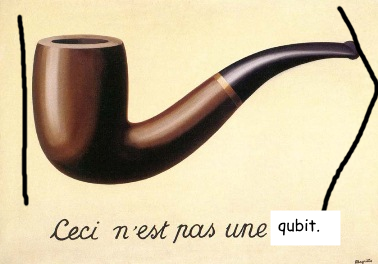

This is Not a Qubit

08 Sep 2019The Map is Not The Territory

There’s a classic observation in philosophy that “the map is not the territory.” Though it sounds obvious enough to take entirely for granted, this observation reminds us that there is a difference between the world around us and how we choose to represent that world on a map. Depending on what we want to use the map for, we abstract away many different properties of the real world, such as reducing the amount of detail that we include (we clearly can’t include every object in the real world in our maps). We may even add things to our map that don’t actually exist in the world, but that we find useful at a social level, such as national borders. In all cases, we make these choices so that our model of the world (a map) lets us predict what will happen when walk around the world. We can use those predictions to trade off different possible routes, guess at what might be an interesting place to visit, and so forth.

The lesson learned from separating maps from the world becomes far less obvious, however, when we are working with realities and abstractions that are less familiar to us. It’s quite easy, for instance, for both newcomers and experienced quantum physicists to accidentally conflate a register of qubits with the model we use to predict what that register will do. In particular, if we want to simulate how a quantum program transforms data stored in a register of qubits, we can write down a state vector for that register, then use a simulator to propagate that state vector through the unitary matrices for each instruction in our program.

As an example, we can use tools like Q# and the Quantum Development Kit to understand how a quantum program can cause two qubits in a quantum register to become entangled. Using IQ# with Jupyter Notebook, we might something like the following (run online):

In [1]: open Microsoft.Quantum.Diagnostics;

... open Microsoft.Quantum.Measurement;

...

... operation DemonstrateEntanglement() : (Result, Result) {

... using ((left, right) = (Qubit(), Qubit())) {

... H(left);

... CNOT(left, right);

...

... DumpMachine();

...

... return (MResetZ(left), MResetZ(right));

... }

... }

Out[1]: DemonstrateEntanglement

Here, we’ve defined a new operation that asks for two qubits, then runs the H and CNOT instructions on those qubits.

The call to DumpMachine asks the simulator to tell us what information it uses internally to predict what those instructions do, so that when we do the measurements at the end of the program, the simulator knows what it should return.

Looking at the output of this dump, we see that the simulator represents left and right by the state $\left(\ket{00} + \ket{11}\right) / \sqrt{2}$:

In [2]: %simulate DemonstrateEntanglement

# wave function for qubits with ids (least to most significant): 0;1

∣0❭: 0.707107 + 0.000000 i == ***********

[ 0.500000 ] --- [ 0.00000 rad ]

∣1❭: 0.000000 + 0.000000 i ==

[ 0.000000 ]

∣2❭: 0.000000 + 0.000000 i ==

[ 0.000000 ]

∣3❭: 0.707107 + 0.000000 i == ***********

[ 0.500000 ] --- [ 0.00000 rad ]

Out[2]: (One, One)

It might be then tempting to conclude that left and right are the state $\left(\ket{00} + \ket{11}\right) / \sqrt{2}$, but this runs counter to what we learned from the example of separating maps of the world from the world itself.

To resolve this, it helps to think a bit more about what a quantum state is in the context of a quantum program.

For starters, if I give you a copy of the state of a quantum register at any point in a quantum program, you can predict what the rest of that quantum program will do.

Implicit in the word “copy,” however, is that the state of a quantum register is a classical description of that register.

After all, you can’t copy a register of qubits, so the fact that we can copy the state is a dead giveaway that state vectors are a kind of classical model.

That classical model is a pretty useful one, to be fair; it not only lets you simulate what a register of qubits will do, but also lets you prepare new qubits in the same way, using techniques like the Shende–Bullock–Markov algorithm (offered in Q# as the Microsoft.Quantum.Preparation.PrepareArbitraryState operation).

Put differently, while the No-Cloning Theorem tells us that we can’t copy the data encoded by a quantum register into a second register, we can definitely copy the set of steps we used to do that encoding, then use that recipe to prepare a second register. Perhaps instead of saying the map is not the territory, then, we should say that the cake is not the recipe! While I can use a recipe to prepare a new cake, and to understand what should happen if I follow a particular set of steps, it’s difficult to eat an abstract concept like a recipe and definitely not very tasty. It’s also pretty difficult to turn one cake into two, but not that hard to bake a second cake following the same recipe.

The Cake is Not a Lie

Thinking of a quantum state as a kind of recipe I can use to prepare qubits, then, what good is a quantum program? To answer that, let’s look at one more example in Q#:

In [3]: open Microsoft.Quantum.Diagnostics;

... open Microsoft.Quantum.Measurement;

... open Microsoft.Quantum.Arrays;

...

... operation DemonstrateMultiqubitEntanglement() : Result[] {

... using (register = Qubit[10]) {

... H(Head(register));

... ApplyToEach(CNOT(Head(register), _), Rest(register));

...

... DumpMachine();

...

... return ForEach(MResetZ, register);

... }

... }

If we were to run this one, the simulator would dump out a state with $2^{10} = 1,024$ amplitudes, but it’s much easier to read and understand what that program does by looking at the Q# source itself.

From that perspective, a quantum program can help us understand a computational task by compressing it down from a description purely in terms of state vectors, focusing back on what we actually want to achieve using a quantum device.

The simplest and by far the most effective way to both achieve this compression is to simply write down the instructions we need to send to a quantum device to prepare our qubits in a particular state.

Thus, instead of writing $\ket{+}$, for instance, we write down the program H(q).

Instead of writing down $\ket{++\cdots+}$, we write down ApplyToEach(H, qs).

Instead of writing down a state vector for each individual step in a phase estimation experiment, we write a program that calls EstimateEnergy.

This has the massive added advantage that we can optimize our quantum programs; that is, we can write down a sequence of instructions that utilizes what we know about the task we’re trying to achieve to use as few quantum instructions as possible.

Indeed, the cake–recipe distinction is especially important as we consider actual quantum devices. In order to solve interesting computational problems using quantum computers, we want to be able to measure actual qubits, and get useful answers back. At that scale, writing down and thinking only in terms of state vectors simply isn’t possible. We need instead to focus on what we actually want to do with our qubits. Once we do that, we’re in a much better spot to have our cake and eat it, too.

If you liked this post, you’ll love Learn Quantum Computing with Python and Q#, now in early access preview from Manning Publications. Check it out!